It’s a question that feels somehow inevitable, (however cynical it might be).

As my colleague put it in a post of ours in late May, “could it be that alien life came to earth in search of intelligent life, found that the dominant species knew it was intentionally destroying their planet […] and simply turned around and went home?”

Failure to Act

After all, the climate news on our planet continues to be, shall we say, not good.

One such example was this recent report in The New York Times that, as Utah’s Great Salt Lake continues its catastrophic shrinking, “the air surrounding Salt Lake City [will] occasionally turn poisonous.” This is due to high levels of arsenic in the now-exposed lake bed, which, as that lake bed dries, will be carried on the wind into the air around Salt Lake City.

According to The Times, “As climate change continues to cause record-breaking drought, there are no easy solutions. Saving the Great Salt Lake would require letting more snowmelt from the mountains flow to the lake, which means less water for residents and farmers. That would threaten the region’s breakneck population growth and high-value agriculture — something state leaders seem reluctant to do.”

On the Precipice

The drying up of lakes and rivers is, of course, bad. Destruction of natural ecosystems has impacts reaching up and down the food chain, not least our own human homes becoming less and less habitable.

But the Great Salt Lake is different. It’s more. According to The Nature Conservancy, “Scientists and conservationists have long known the Great Salt Lake’s value. It is one of only a few places on Earth that can meet the food and shelter needs of millions of birds traveling along the Eastern Spur of the Pacific flyway—a migratory route spanning the Northern and Southern hemispheres. Winging their way from places as far as South America and northern Canada, up to ten million birds are drawn to the Lake each year—many representing the largest gatherings of certain species in the world.”

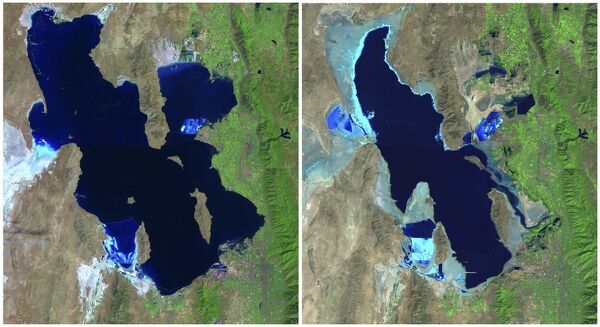

And, again according to The Times, “Last summer, the water level in the Great Salt Lake reached its lowest point on record, and it’s likely to fall further this year. The lake’s surface area, which covered about 3,300 square miles in the late 1980s, has since shrunk to less than 1,000, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.”

Wild solutions

Yet, Utah is not ready to make real sacrifices to save their Great Salt Lake.

As relocation West continues to cause water-use to spike in desert regions like Utah, Nevada, and Southern California, a historic drought, amplified by climate change, has dramatically reduced the amount of available water. Booming cities are vying with farms, rivers, lakes, and animal populations for precious groundwater. But rather than mandate serious restrictions on water-use by city-dwellers, Utah lawmakers are exploring a billion dollar pipeline to pump ocean water from the Pacific to the Great Salt Lake. (Never mind that increased salinity is already a grave problem for the Lake, which maintains its saline balance by being fed freshwater from rivers and streams.)

According to The Salt Lake Tribune, “A better option would be for Utah to figure out how to use less water, so more of the Bear, Weber and Jordan rivers reach the lake, said Friends of Great Salt Lake Executive Director Lynn de Freitas. A pipeline would not only degrade the landscape it crosses but would also disrupt the terminal lake’s chemistry.”

Use less?

Consider the impacts of our choices — to have green lawns, sprawling neighborhoods inside of cities that themselves have grown beyond what can be supported by available local resources — and, perhaps, reconsider?

Or, (despairingly more likely), simply adapt to a life where clouds of poisonous dust are an occasional feature.